Published in October 2 New Braunfels Herald-Zeitung (subscription required)

This past weekend, my nine-year-old son and I enjoyed hiking Landa Park’s Panther Canyon Nature Trail, checking out Comal Springs, and floating the Comal River—being careful to keep our distance from others on the trail and river.

While pausing to reflect at the springs (the largest in Texas and the southwestern United States), my son asked where the water was coming from.

Area signs and diagrams illustrated how water generally flows underground from higher elevations in the Edwards Aquifer recharge and contributing zones. But where exactly does Comal Springs water originate?

The answer isn’t a simple one, but over the past few decades, hydrogeologists have learned that the water naturally surfacing at area springs (Comal, Hueco, San Marcos) largely starts as rainfall over the recharge zone west and southwest of New Braunfels, including the area that drains into Dry Comal Creek (between Interstate 35 and Highway 46).

The Edwards Aquifer consists of a network of subsurface cavities, streams, and channels. These underground rivers quickly transport large volumes of precipitation over the recharge zone through sinkholes, fractures, and caverns to features such as Comal Springs.

In Landa Park, we seemed to be a world away from the dusty and barren strip of quarries, concrete batch plants, and cement facilities just southwest of New Braunfels along Interstate 35.

But was there an underground connection linking these disparate locations?

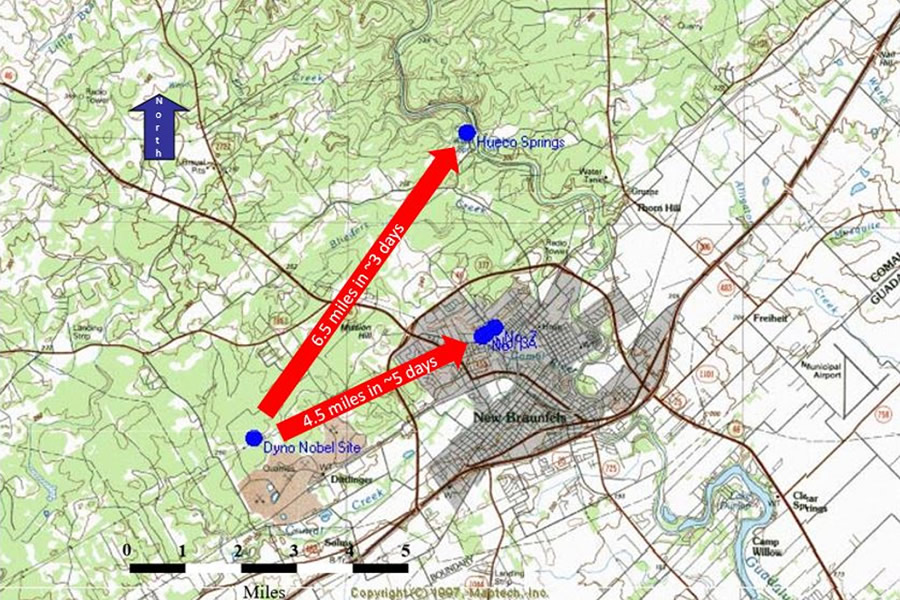

Indeed, in 2000, an event occurred at the New Braunfels Cemex quarry that demonstrated just how interconnected Comal and Hueco Springs—and our drinking water supply—are to the many aggregate mining facilities in Comal County. During the weekend of January 16, an estimated 2,800 gallons of diesel fuel leaked from a Dyno Nobel storage tank at Cemex into the Edwards Aquifer recharge zone. Employees didn’t discover the leak until Monday morning and didn’t report it until Tuesday. Cleanup began on Wednesday, but the mitigation effort was evidently too little—and too late.

By then, measurable amounts of volatile and semi-volatile organic compounds (VOCs and SVOCs) such as 2-methyl naphthalene, naphthalene, and xylenes had already started showing up in both Comal Springs and Hueco Springs. In a matter of days, the spilled diesel fuel apparently entered the karst aquifer and traveled underground, contaminating water several miles away.

Unfortunately, this wasn’t an isolated incident. Aquifer contamination from an 800-gallon gasoline spill in northern Bexar County precipitated the closure of several private wells. Tetrachloroethene (PCE) leaked into the aquifer near Uvalde in 1979—and that contamination plume is still being detected in groundwater samples four decades later.

In June of this year, a tailings pond dike at the Anderson Columbia quarry, located over the recharge zone between New Braunfels and Garden Ridge, collapsed, allowing polluted water from mining and quarrying operations to flood neighboring properties. TCEQ investigated and sent notices of violation. But the toxicity level of the escaped liquid is apparently still unknown—and the damage was already done.

If we follow Dry Comal Creek upstream to the West Fork, past FM 1863 and along FM 3009, we come to the proposed site of a new, 1500-acre quarry. Since 2017, Alabama-based Vulcan Materials has been trying to convert the former White Ranch into an open-pit limestone mine that would stretch nearly three miles across the recharge zone. So far, efforts of community volunteers opposing this quarry have prevented the start of mining operations.

Jack Olivier, a Comal County geologist, recently stated that “quarries here can act as manmade funnels into the underlying aquifers. The limestone sediment and explosives used for blasting, a combination of diesel fuel and ammonium nitrate, can be introduced inside the pits.”

As we continue to learn more about the Edwards Aquifer, one of the most environmentally sensitive features in Texas, it becomes increasingly clear that this area is the place for parks, hiking trails, and open space—not more quarries. High-risk industrial operations and hazardous chemicals jeopardize the primary water supply for over two million people and endanger unique and beautiful features such as Comal Springs.

Landfills are already prohibited over the recharge zone. The time has come to prohibit additional quarries and aggregate mines as well. Non-profit organizations such as Preserve Our Hill Country Environment, Texans for Responsible Aggregate Mining, Hill Country Alliance, and Greater Edwards Aquifer Alliance; and neighboring Hays County are at the vanguard of the effort to protect our water and preserve open spaces. It’s high time our county and state elected officials join in.

As my son and I tubed the Comal River later that day, we noticed something quite unpleasant: a dead turtle floating in the water. I couldn’t help but wonder if that was a harbinger of things to come in Comal County.

David A. Drewa

Director of Communications

Stop 3009 Vulcan Quarry

Preserve Our Hill Country Environment

Related Video

Related News

Tuesday Hearing Set for Comal Vulcan Quarry Air Permit Appeal

December 6, 2020

Legal hearing on Friends of Dry Comal Creek v. TCEQ (Vulcan air permit) will be held December 8, 2020, in 459th District Court, Travis County.

Trial Portion of Hearing on Proposed Comal Quarry Concludes

June 13, 2019

The hearing on the merits against Vulcan Construction Materials has ended. SOAH judge plans to render decision in case by September 3, 2019.

Key Hearing on Proposed Comal Vulcan Quarry Starts June 10

June 5, 2019

Contested case hearing to determine TCEQ action on air quality permit application for Vulcan quarry between Bulverde and New Braunfels.